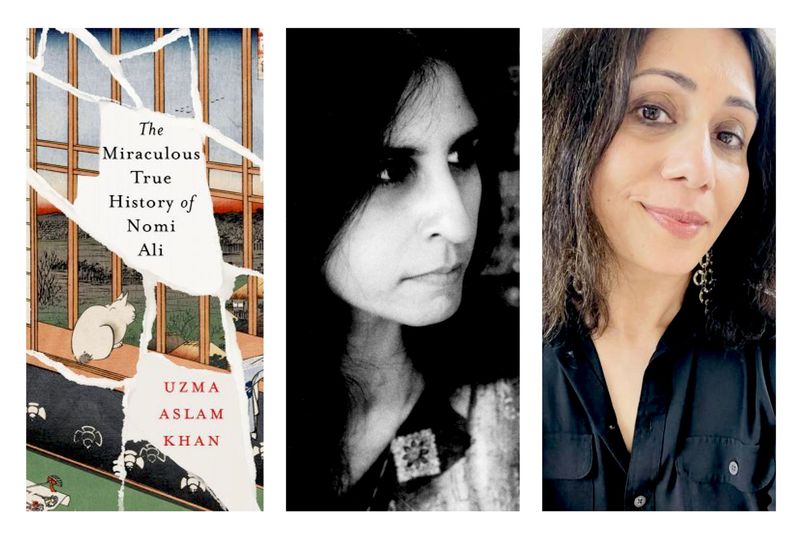

Conversation with writer Uzma Aslam Khan at McNally Jackson Seaport in NYC

Honored to engage in conversation with the brilliant Uzma Aslam Khan about her new book, The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali, on June 28th (7:00pm) at McNally Jackson Seaport (4 Fulton Street) in NYC.

Beautifully written and part of the important process of decolonizing history and literature, Uzma’s book brings to life revolutions that have been erased and forgotten, and exposes (oh so eloquently) the mechanics of colonial oppression. It’s a stunning book that demands a rich convo.

Learn about “interventions of knowing” that subvert the colonial script. Learn about exile, imprisonment and resistance. From the book:

“She tries to remember colours, sunlight, the breezes that tease the crops of open fields. She tries to catch new rain on her tongue. She tries to remember the song of the koel. She tries to forget what she has left. This effort to remember and to forget comes like the waves she cannot hear but can feel, they are there, under her chains. If she could look outside, just once.”

Pls join us for a discussion, reading and book signing in NYC. Tickets are available here.

My questions for Uzma:

1) The Miraculous True History of Nomi Ali is an extraordinary novel set in the Andaman Islands in the 1930s and 1940s. The islands are located at the edge of the Bay of Bengal, east of the Indian subcontinent, and were popularly known as kala pani, which means black water.

The British built a prison system there to exile and punish political prisoners. These were colonized people from South Asia creating too much trouble for the British empire.

Many times I am struck by the dissonance between beauty and violence.

In your book you describe the Andaman Islands and their lushness in wonderful detail.

You write about swiftlets, hornbills, papaya and fig trees, shrews, mangroves, a breeze that ruffles the creek such that turquoise and teal surface (colours to soothe the eye). You write about sounds like the click of bamboo, the bicker of parakeets, and the edginess of the sea. How there are names for each wind. The Yellow Angel. The Praying Mantis. The Father. The Friend. How the ocean flies through the trees.

And yet, this is a penal colony where countless people are imprisoned, maimed, killed, and their families deliberately impoverished.

Was this contrast between landscape and human brutality important to you? How did it figure in the writing of the book?

2) Infrastructures of oppression always reserve a special kind of barbarity for women. This was certainly the case on the Andaman Islands. But some of the most important and fascinating characters in your book are women. There is Nomi of course, the book’s protagonist, but there is also prisoner 218 D, a political prisoner who is part of the Indian resistance to British rule. Then there is Shakuntala whose history and circumstances are quite unique.

Could you tell us about how you found these characters and the crucial space they occupy in the book?

3) Colonialism can be spectacularly violent, meaning starvation, torture, rape, collective punishment, forced labor, even medical experiments on prisoners and their families.

But colonialism is also quiet violence. Something insidious that warps human relationships. Franz Fanon wrote about this extensively.

You have captured the intimacy of this violence most vividly through the relationship between Aye, one of the main characters in the book, and the jail superintendent Mr Howard. It summarizes the uneven bond between colonizer and colonized so astutely, so skillfully.

Could you pls talk about bringing that relationship to life?

4) Voice, language, and histories are important themes in the book. Let me share a couple of examples:

“Somewhere in the great sky beyond this sky of planes was a star, made entirely of words. And on the star lived as many different kinds of words as birds in all the skies, fish in all the seas, and clay patterns in all the hands of adoring women. Some words were cautious as the crabs nesting on the beach. Others, bold as the giant hornbills prattling in the trees. Then there were those that made no sound, but were equally fearless, folding their arms and waiting for her to sit on their lap.”

In another paragraph you say:

“It was here, at the edge of the abyss, that he had found a kind of ritual. The repetition of dates of a forgotten past, a past not taught at school. He recited them as a prayer before descending into the cave, perhaps to keep from slipping through time.”

I would love to hear your thoughts about language – how do u conceive of it, tame it, deploy it, reach for it as a writer?

And talking about language, there are also some beautiful passages that capture the ache and nostalgia of exile.

Again, I’ll quote from the book:

This is about prisoner 218D: “She tries to remember colours, sunlight, the breezes that tease the crops of open fields. She tries to catch new rain on her tongue. She tries to remember the song of the koel. She tries to forget what she has left. This effort to remember and to forget comes, like the waves she cannot hear but can feel, they are there under her chains. If she could look outside just once.”

This is Haider Ali, Nomi’s father: “The sun that rose the next morning, my first and only morning as a free man on this rock, it was the most beautiful thing I have ever seen. If only I could describe for you the colours and flavours of apricots and loquats. That is how the sun looked. Delicious…”

I was thinking that you too know something about being uprooted and displaced. How do such transgressions across borders, such wistful longings and memories, shape ur writing?

5) Something that moved me immensely in the book, is how gently and lyrically you write about people who are endlessly violated and traumatized.

You write about Aye’s grandfather:

“His voice was a deep rumble and Aye loved it, the cadences of warmth and wisdom that flew as untidily as his beard and without cease.”

This is Nomi’s father once again, Haider Ali, who is a convict:

“He wants his children to have a heart expansive enough to hold the sky. He wants birds of every vibrant colour to fly within the limitless confines of their heart. He wants each bird to carry in its beak a precious gift. In one, love. In another, laughter. In a third, hope. In a fourth, a bracelet for using their hands well. In a fifth, the bond between siblings.”

You describe Aye’s feet, beautiful and arched, and his hands which “could unmap the grooves of time.”

Then there is Nomi, “the keeper of seas that flowed into each other and into her bowl.”

How did you flesh out these characters in such metaphorical ways?

6) This question is a bit hard for me to articulate, but I felt like the lives – the very survival of the prisoners, their families, and the indigenous people of the islands, was a zero sum game. That one life had to be extinguished in order for another to pull through. I won’t give examples because I don’t want to give too much away, but it felt like some of the most marginalized and imposed upon people in the world are offered fewer life-slots to hold on to. Not all can be accommodated. Yet this scarcity of life, this inescapable demand for sacrifice, also ties them together in astonishing ways.

Was this part of the complex, multi-layered storyline you constructed?

7) In the acknowledgments, at the end of the book, you write:

“To my father, who taught me to look at power, and never forget. This book is for him.”

It’s such an intriguing tribute. Could you tell us more about your father?

8) I learned a great deal about resistance to colonial rule in this incredible book. For example, I didn’t know that the transformation of the islands into a penal colony really began after the war of independence (what the British call the Great Mutiny) in 1857, and that a large portion of the prisoners were political prisoners. I didn’t know about revolutionary poets like Ram Pradad Bismil and Asrar ul Haq. I didn’t know that prisoners on the island went on hunger strikes to protest their brutal circumstances and that those protests were supported and mirrored on the mainland, in India, where people were also fighting for freedom.

Could you tell us about how you gleaned this important history from the archives?

Leave a comment